I send this newsletter every Friday morning. Subscribe for free here. In this week’s issue:

💡 Ideas:

Apple’s New Updates,

Are Tech Tools Neutral?

📖 Interesting Links:

Wrongfully accused by an algorithm,

Workhuman is a unicorn,

Fact-checking Fake Images,

Citizen neuroscience.

🎧 Podcast Recommendation:

How Facebook Is Undermining ‘Black Lives Matter’

💡 Ideas

Apple’s New Updates.

On Monday Apple had their annual developer conference, with lots of interesting tech changes announced. Here’s some of the more interesting one from a public policy perspective:

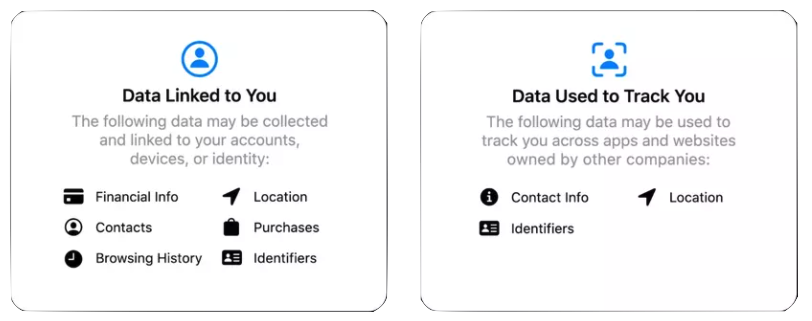

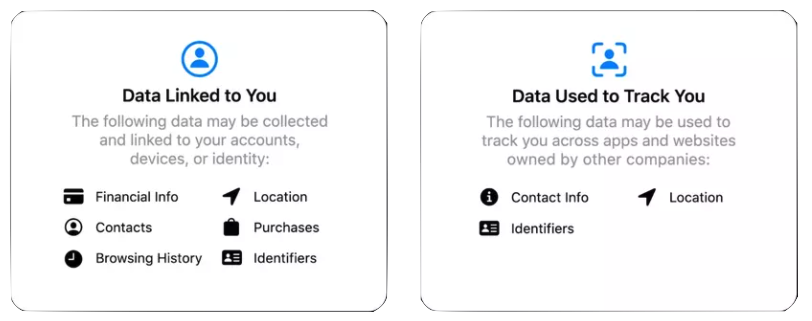

1. They’re re-designing the way apps ask for your data. They want to balance information that is both comprehensive, but also easy to understand and digest. If someone can’t understand what they’re agreeing to, can they really consent? Apple talks about its new labelling system like a nutrition label on food, and I think it’s a big step in the right direction.

2. They’ve also given more power to users in the ways they share data, with the options to give an app access to a single picture, rather than the whole library, to grant approximate location so an app can know roughly, but not exactly, where you are. There’s also a mic/camera indicator on phones (like the green light on your laptop’s webcam) that will let you know an app is using your microphone or camera.

3. They have a few extra “good corporate citizen” updates – The Safari browser will show how many trackers and cookies it blocks on each website, Apple Watch prompts to wash your hands and Memoji wearing face-masks. Read more.

Are Tech Tools Neutral?

One expression that techies love (myself included) is that “tech is neutral.” Tools in general are neutral, a hammer can be used to build a house or kill a person. The intent of the user can be good or evil, but the tool itself is neutral.

Scratching one layer beneath the surface and it’s clear that tools and tech aren’t always entirely neutral. The paper “Do Artefacts Have Politics?” published in 1980 by Langdon Winner suggests that, while of course the intent of the user and the social context in which it is used matters, it’s also true that “artefacts can contain political properties.” He says:

“At issue is the claim that the machines, structures, and systems of modern material culture can be accurately judged not only for their contributions of efficiency and pro ductivity […] but also for the ways in which they can embody specific forms of power and authority.”

“Consciously or not, deliberately or inadvertently, societies choose structures for technologies that influence how people are going to work, communicate, travel, consume, and so forth over a very long time. In the processes by which structuring decisions are made, different people are differently situated and possess unequal degrees of power as well as unequal levels of awareness.”

He breaks the possible ways in which technologies are political into two categories. In the first, flexible technologies have a range of choices for how they can be implemented and adopted, and these choices can have political significance. In the second, the mere adoption or creation of a technology has consequences for the way it re-structures power and authority around it.

In the first instance, the configuration of a technology is political. Broadband cables may be neutral, but we shift economic power towards communities where we install it, and away from communities that we don’t.

Some choices are less obvious and intentional. Every tech service that doesn’t make itself accessible to those with disabilities has (often unintentionally) removed power and access from already marginalised communities – not just from the tech, but from jobs, relationships and active citizenry that they enable.

On the flip side, look at the “sound recognition” features Apple announced this week, which alert deaf users to sounds the phone hears like “baby crying” and “smoke alarm.”

“Technological innovations are similar to legislative acts or political foundings that establish a framework for public order that will endure over many generations. For that reason, the same careful attention one would give to the rules, roles, and relationships of politics must also be given to such things as the building of high ways, the creation of television networks, and the tailoring of seemingly insignificant features on new machines. The issues that divide or unite people in society are settled not only in the institutions and practices of politics proper, but also, and less obviously, in tangible arrangements of steel and concrete, wires and transistors, nuts and bolts.”

In his second category of technologies, he’s talking about the political changes in society that new technologies create around themselves. One interesting example he gives is nuclear power vs. solar.

If a nation decides to adopt nuclear technology, certain forms of government are almost a necessity. “If you accept nuclear power plants, you also accept a techno-scientific-industrial military elite. Without these people in charge, you could not have nuclear power.”

Solar Power, on the other hand, can be decentralised and localised. You could imagine ways in which that technology would empower individuals to be less reliant on the military-nuclear state or economically reliant on the company that owns the coal plant. Or, you can imagine communities and local authorities managing power generation locally and using the proceeds from it to fund local projects. What if wind power generation was considered a local natural resource and taxed at the local level?

Social Media Platforms can be considered for the way they restructure political power too. They caused the collapse of many traditional gatekeepers. These include newspaper editors and TV anchors, but also incumbent politicians, large advertisers and religious leaders. The printing press and broadcast TV and mass advertising technologies structured power in their favour in a way that the internet does not.

As they are no longer the primary gatekeepers of information, their loss of power and influence (and many times, moderation) has restructured society, as has the increase in power gained by the average citizen, artist, small business and new political candidate.

Of course, as the social networks have dismantled the power of old gatekeepers and distributed it to individuals, they have also accrued vast amounts of it for themselves as the new algorithmic gatekeepers.

“The things we call ‘technologies’ are ways of building order in our world.”

“The adoption of a given technical system unavoidably brings with it conditions for human relationships that have a distinctive political cast. For example, centralized or decentralized, egalitarian or inegalitarian, repressive or liberating.”

“Taking the most obvious example, the atom bomb is an inherently political artifact. As long as it exists at all, its lethal properties demand that it be controlled by a centralized, rigidly hierarchical chain of command closed to all influences that might make its workings unpredictable. The internal social system of the bomb must be authoritarian; there is no other way. The state of affairs stands as a practical necessity independent of any larger political system in which the bomb is embedded, independent of the kind of regime or character of its rulers. Indeed, democratic states must try to find ways to ensure that the social structures and mentality that characterize the management of nuclear weapons do not “spin off’ or “spill over” into the polity as a whole.”

This is true for the structures of government that manage technologies, but also for the kinds of companies that produce and sell them.

The dominant form of industry in the 1800s, the small family firm, could not manage the new technology of the railroad. It required layers of management and centralised authority to co-ordinate and therefore the modern corporation. Did railroad technology make the modern corporation inevitable? Or put another way, was inventing the corporation the only way society could get the benefit railroads delivered?

We could ask questions like this about Amazon’s size and dominance. Does the very nature of eCommerce demand an Amazon? Are there aspects of online commerce – the economies of scale, the delivery infrastructure, the catalogue – that imply Amazon as the only model of organising authority and power? Or can other models exist – like infrastructure for many small businesses (Shopify or Stripe) or standalone marketplaces (eBay, Etsy).

In this reality, the emergence of eCommerce created a man worth $100bn (Jeff Bezos), but was that inevitable? Could it have happened another way? Do the benefits of eCommerce demand to be managed by a large, centralised and hierarchical organisation?

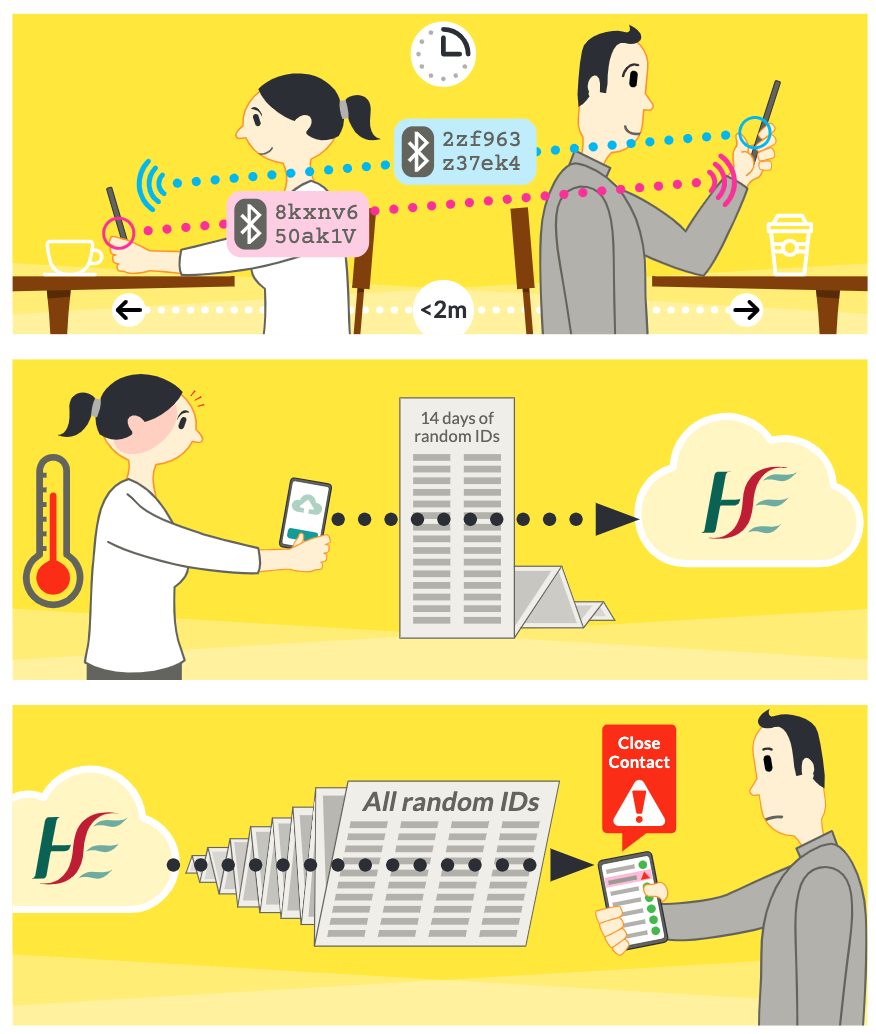

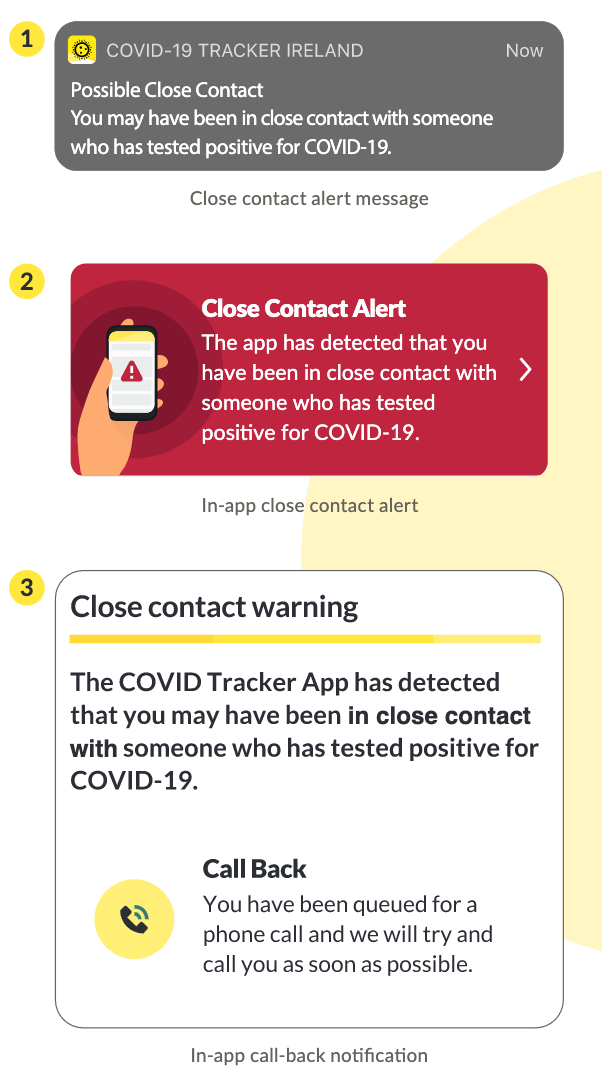

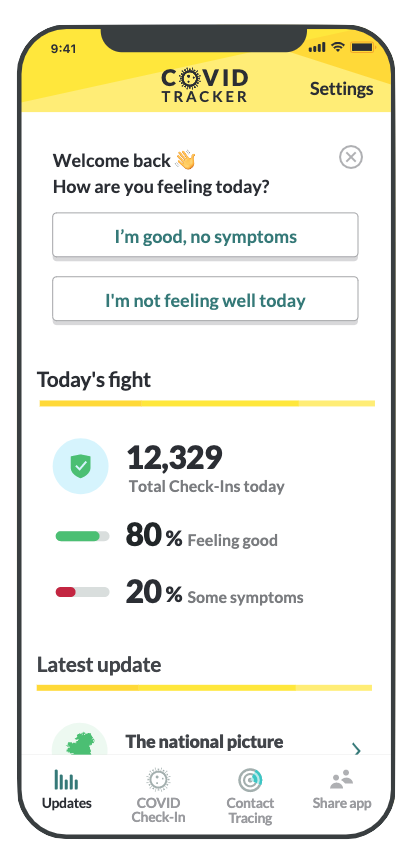

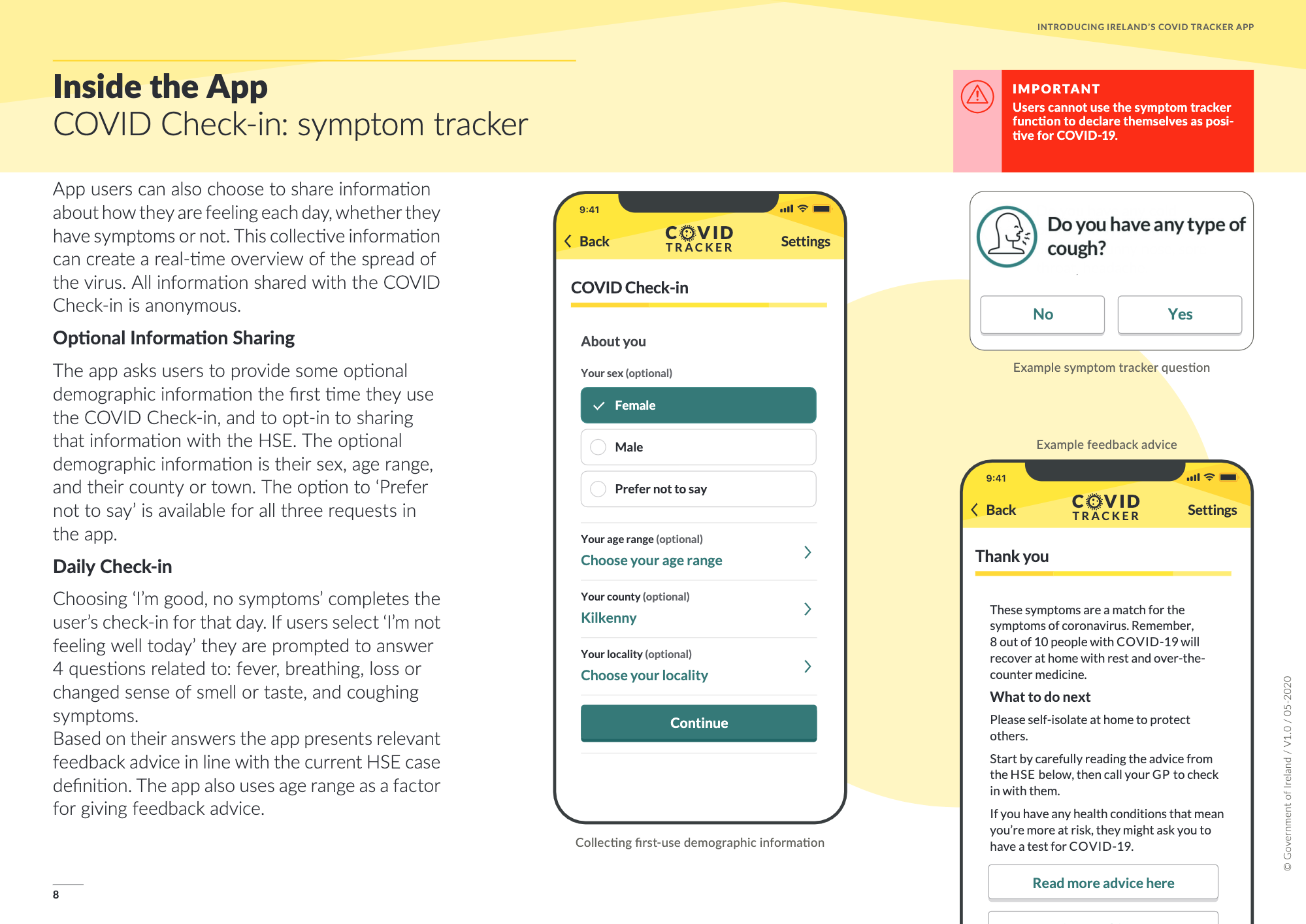

Another interesting modern parallel is the politics of contact-tracing apps for Covid-19. We often focus on the privacy issues inherent (“does the Dept of Health know my GPS location?”), but less so the political systems they shape around them – authorities that can tell citizens where to go, what to wear, how to behave etc.

I’ll give Langdon Winner the last word:

“In our times people are often willing to make drastic changes in the way they live to accord with technological innovation at the same time they would resist similar kinds of changes justified on political grounds. If for no other reason than that, it is important for us to achieve a clearer view of these matters than has been our habit so far.”

📖 Interesting Links

Wrongfully accused by an algorithm. The New York Times reports on a faulty facial recognition match led to a Michigan man’s arrest for a crime he did not commit. Read more.

Workhuman is a unicorn. First Stripe, then Intercom, now Workhuman is the next Irish-run tech company to reach a $1bn valuation (a.k.a a Unicorn). Read more.

Fact-checking Fake Images. Google are now showing fact checking notices on Google Images search results, which is great to see. We often focus so much on social newsfeeds that we forget just how many people perform searches every day, and how large the potential for misinformation is there. Read more.

Citizen neuroscience. “The rise of do-it-yourself (DIY) neuroscience may provide an enriched fund of neural data for researchers, but also raises difficult questions about data quality, standards, and the boundaries of scientific practice.” Read more.

🎧 Podcast Recommendation

How Facebook Is Undermining ‘Black Lives Matter’, an episode from New York Time’s “The Daily”. Link.