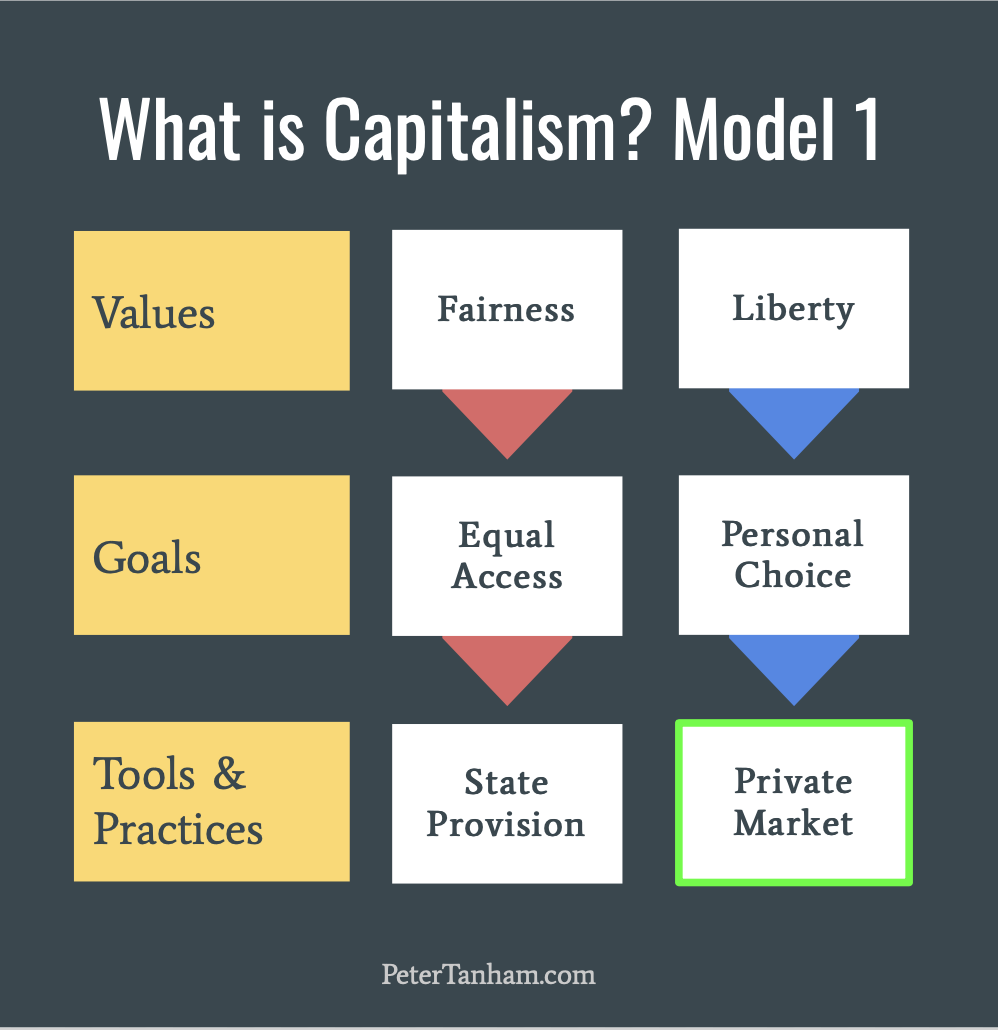

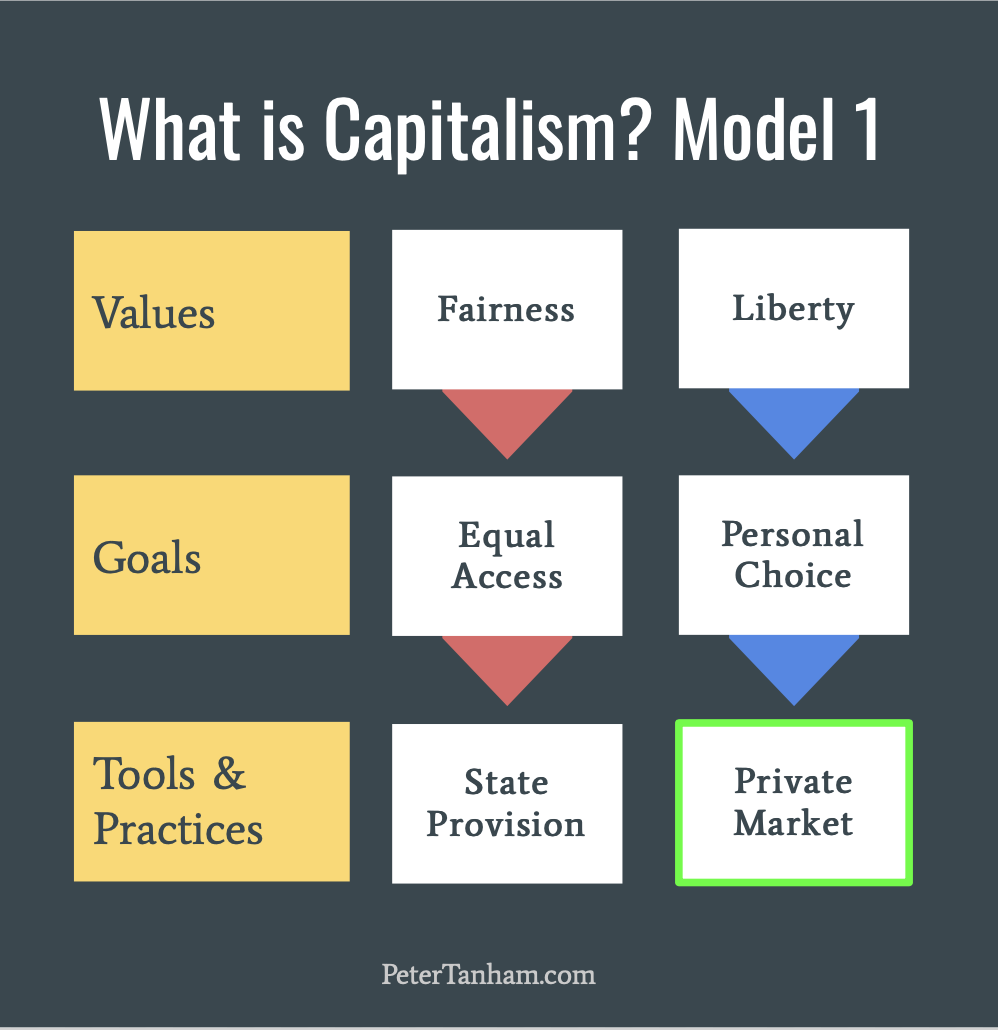

If you were to design a country’s economic model from scratch, there’s a few different places you could start. You might, for instance, start by broadly thinking about the society you want. You’d consider your values and goals, and those of your fellow citizens. You then consider what economic tools and practices have the best track record for achieving those goals.

If you’re thinking about how your economy should deliver healthcare you’d start by saying, for example, “fairness is a key value and a top priority of ours”, and so your goal is probably to provide healthcare on the basis of those who need it most, or where treatment provides the biggest improvement, rather than to those who can most afford it. So you might decide that the state should build and run the hospitals.

On the other hand, “liberty” or “freedom” might be an important value of yours. You might try to express these values by giving people within your society a good range of personal choice, so you might want to create a price-based market for chemists, or non-essential healthcare like orthodontics.

If I was to sketch that approach as a simple framework, it might look something like this:

You start with your values and goals at the top level, then pick the tools and practices that help deliver on them. I’ve highlighted in green where I think “Capitalism” sits in this model – a collection of Tools & Practices, like ‘price-based markets’, ‘free movement of capital’, ‘stock markets’, ‘corporations’, etc..

I think this framework describes broadly the approach of modern progressives, or Democratic Socialists or Market Socialism.

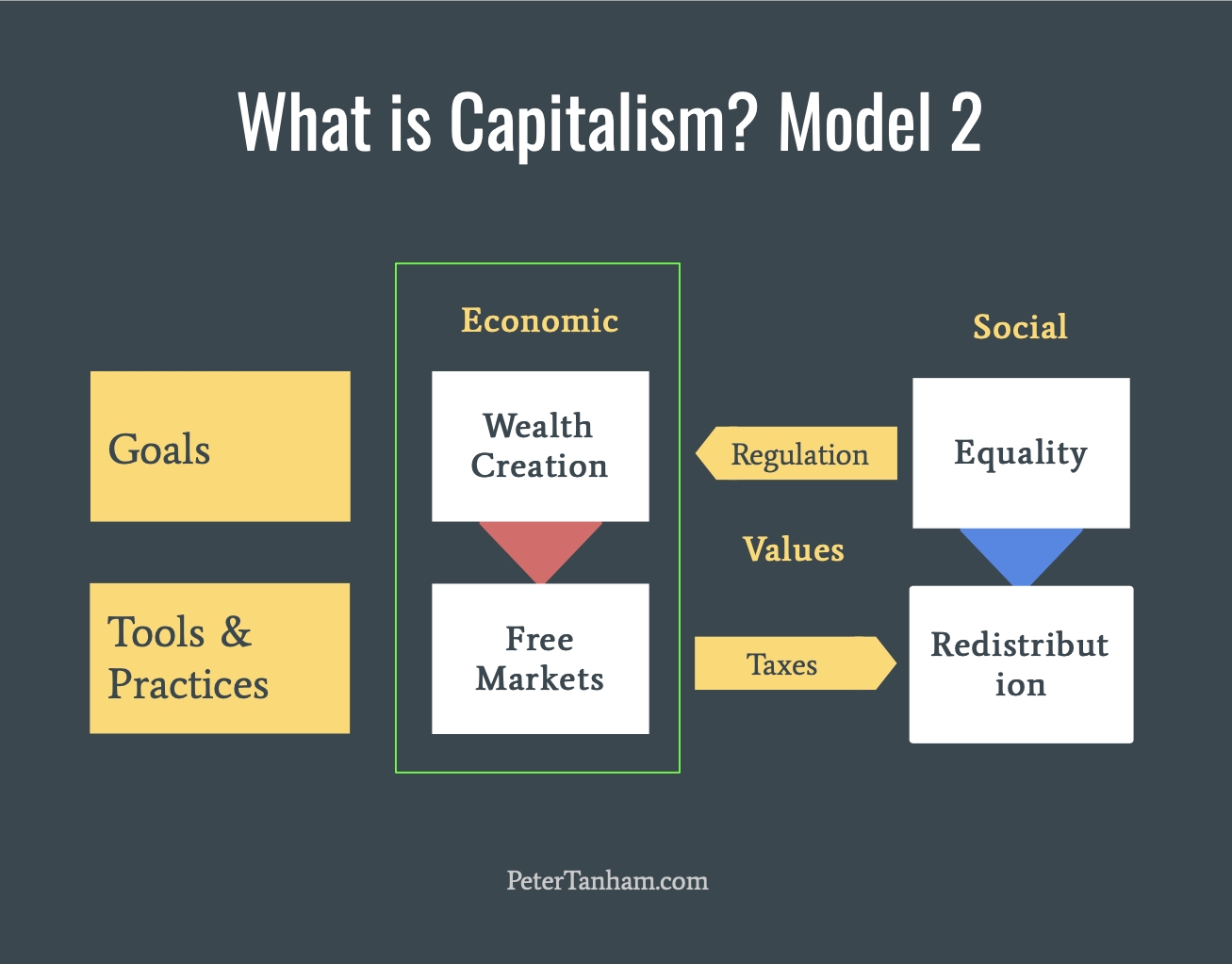

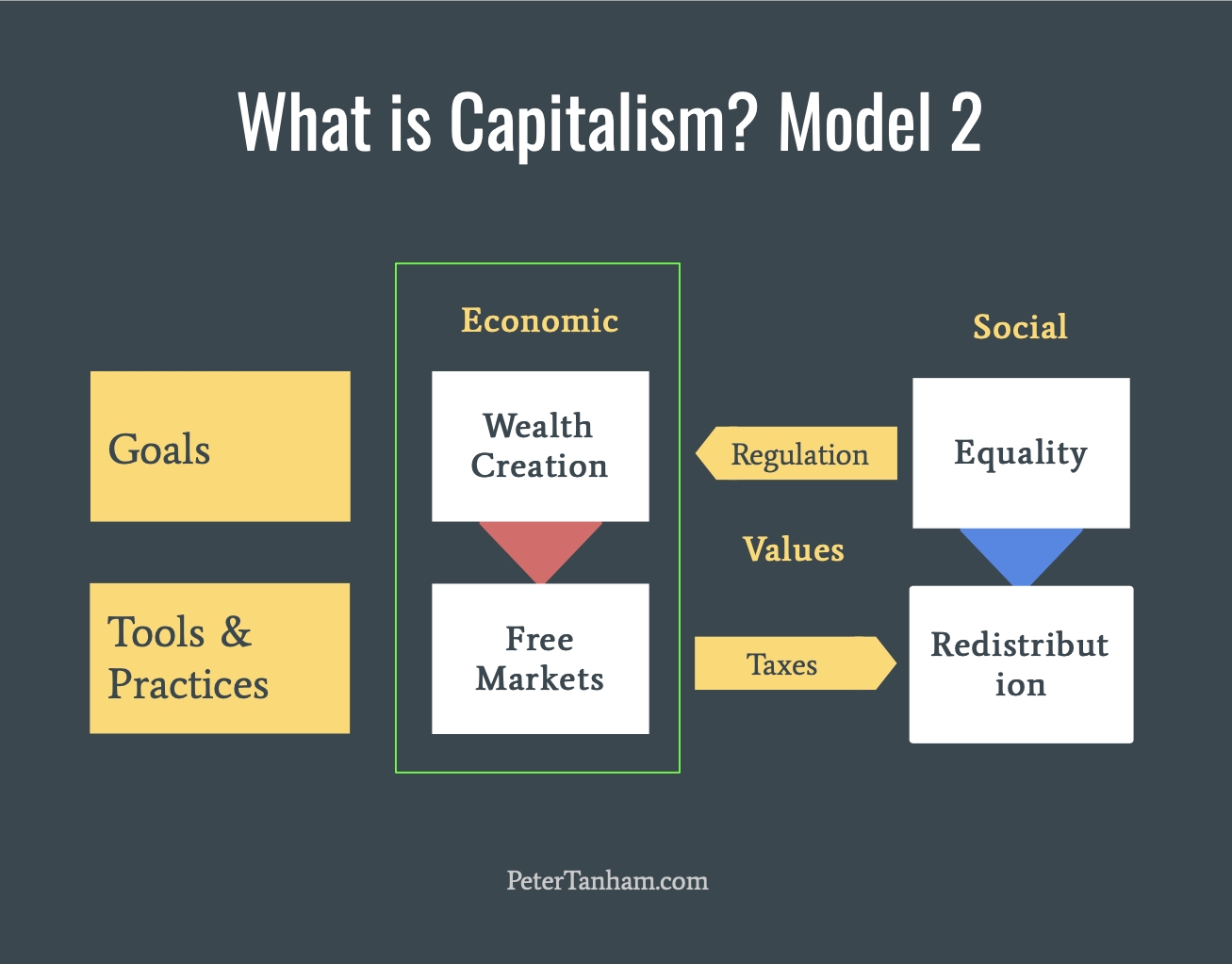

Another place to start when designing your new economy is to say that the tools of Capitalism provide economic growth and prosperity, but it needs a complimentary political system to moderate it’s excesses and redistribute it’s wealth, or to fill in the gaps that Capitalism can’t address. We have Economic issues (the realm of Capitalism) and Social issues (the realm of Government)

In this framing, “Capitalism” is both the tools and the goals. It is the underpinning of all things in the realm of the economy and wealth generation. A social system runs alongside it. Your values might dictate the interaction between the two pillars, even if the contents in each pillar are constant:

This is the framing I believe most of the political centre in Western countries take. Politics is framed as a balancing act between the two. I mostly think this is what “liberals” mean when they talk about Capitalism. A finance sector can earn globs of money, pay some tax, which can fund an NHS. The thinking comes from “the right”, but Bill Clinton and Tony Blair and Barack Obama were electorally very successful operating within this framing.

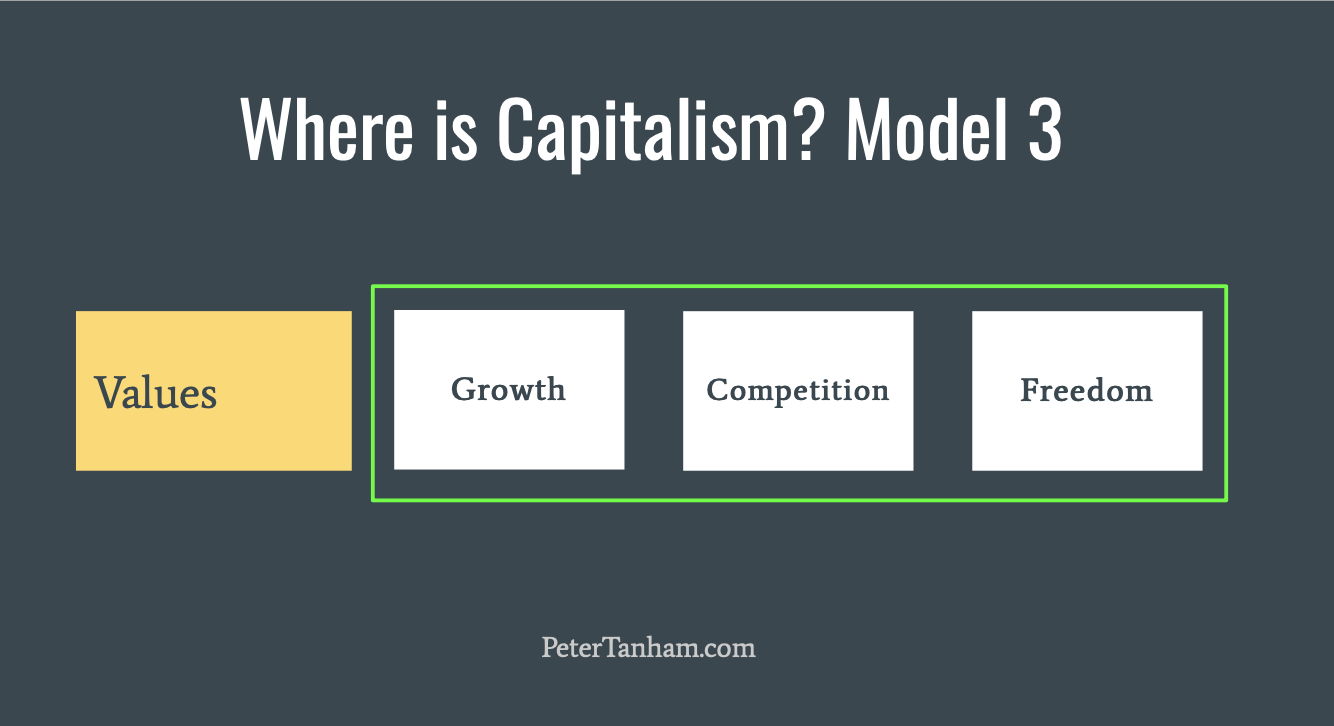

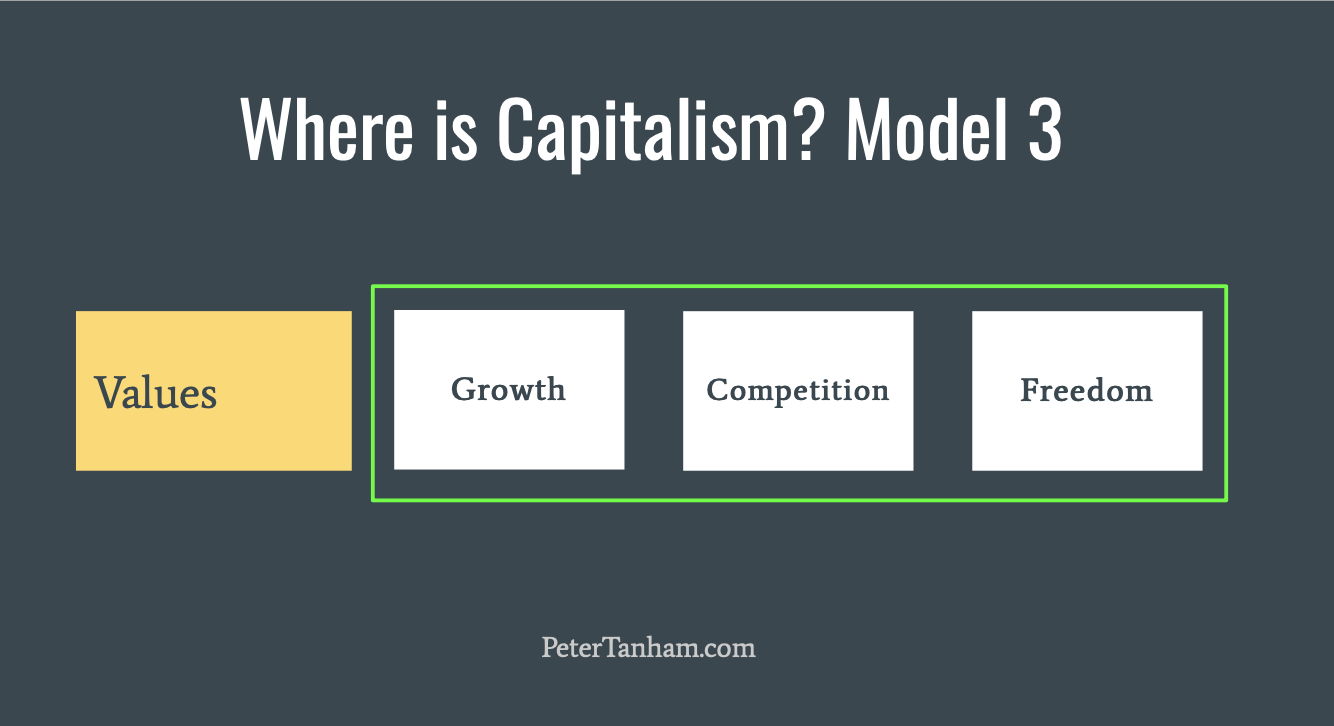

A third approach to designing an economy might be to start with Capitalism as your overall ideology and value set. “Capitalist” is what a country should be. Competition is a core value. Those who have more (because they earned it), get more. Government should be subservient to, and act in service of these values, to defend them with police and armies and rule of law, with enforcing contracts and paying for schools to educate future workforces. Social benefits happen when the Government gets out of the way.

I’m not sure that any modern country operates in this way, but I do believe that it has been a very dominant narrative about how Western countries do (or should) operate. To me, this is the “Capitalism” definition of Regan and Thatcher – something more than just a set of tools or goals, it is a value system and an ideology that must underpin everything.

In many ways, I think “Capitalism as an Ideology” is a powerful framing if you want to shift the balance of power, in the second model, away from the Social pillar and towards the Economic pillar. It makes the question of how you govern Capitalism difficult to ask, and makes a question like “when should you use Capitalism?” seem nonsensical. This is what Regan, Thatcher and others did in the 80s and they were very successful at it.

They shifted the meaning of Capitalism up the value chain, from just a set of tools, to a set of goals and their underpinning ideology. This frame shift was so successful, and so dominant that I think it’s coming back to bite.

It is the framing used by the strongest critics of Capitalism, which leads to a very common debate these days where people are shouting past each other. Someone, who uses “Capitalism” to mean the dominant economic and political ideology, criticises some element of market failure, or regulatory capture, or inequality and gets a lot of support for this view. Then others, who think of Capitalism as either of the first two definitions, are dumbfounded! To them, this is exactly the opposite of what Capitalism is!

Speaking about the baby feeding formula shortage in the US, for example, author Bess Kalb tweeted recently that “The formula shortage is an example of how free market capitalism does exactly what right wing fear-mongers think socialism will do.”

65 thousand people (and bots, I guess) liked this post, but it (and the many other similar statements), also drove some people crazy, pointing out that Capitalism is about “free markets”, and this is not one!

This is how I think about the competing definitions of Capitalism, and how I try navigate conversations with people when I agree that the current system is badly in need of a change (Capitalism as an ideology), but also that many of the same economic tools (Capitalism as a set of tools) will play an important part of any prosperous future we might build.

📰 News

The (mini) resurgence of unions | This week my various newsfeeds have been full of videos of Mick Lynch, the General Secretary of the UK’s National Union of Rail, and his very effective communication style. If you haven’t seen any, here’s a good sample. This level of social media support and virality echoes the successful labor movements in the US earlier this year, with both Amazon and Starbucks workers unionising for the first time.

The new energy in unions is translating into results too, with Unite having won 75% of disputes since their new leader, Sharon Graham, took over eight months ago, according to a great profile in the Guardian.

These developments are very welcome, in my view, because they come at the end of a decades-long decline in the power of organised labour. In Ireland, for example, the CSO Labour Force Survey found 26% of employees were members of a union in 2021, compared with 33% in 2005.

Within this decline is a notable difference between men and women. Both were at 33% in 2005. In 2021, only 22% of men were union members but 29% of women still were, a number that has remained fairly constant over that period. A UCD Smurfit School report published in the Irish Times last weekend found similar.

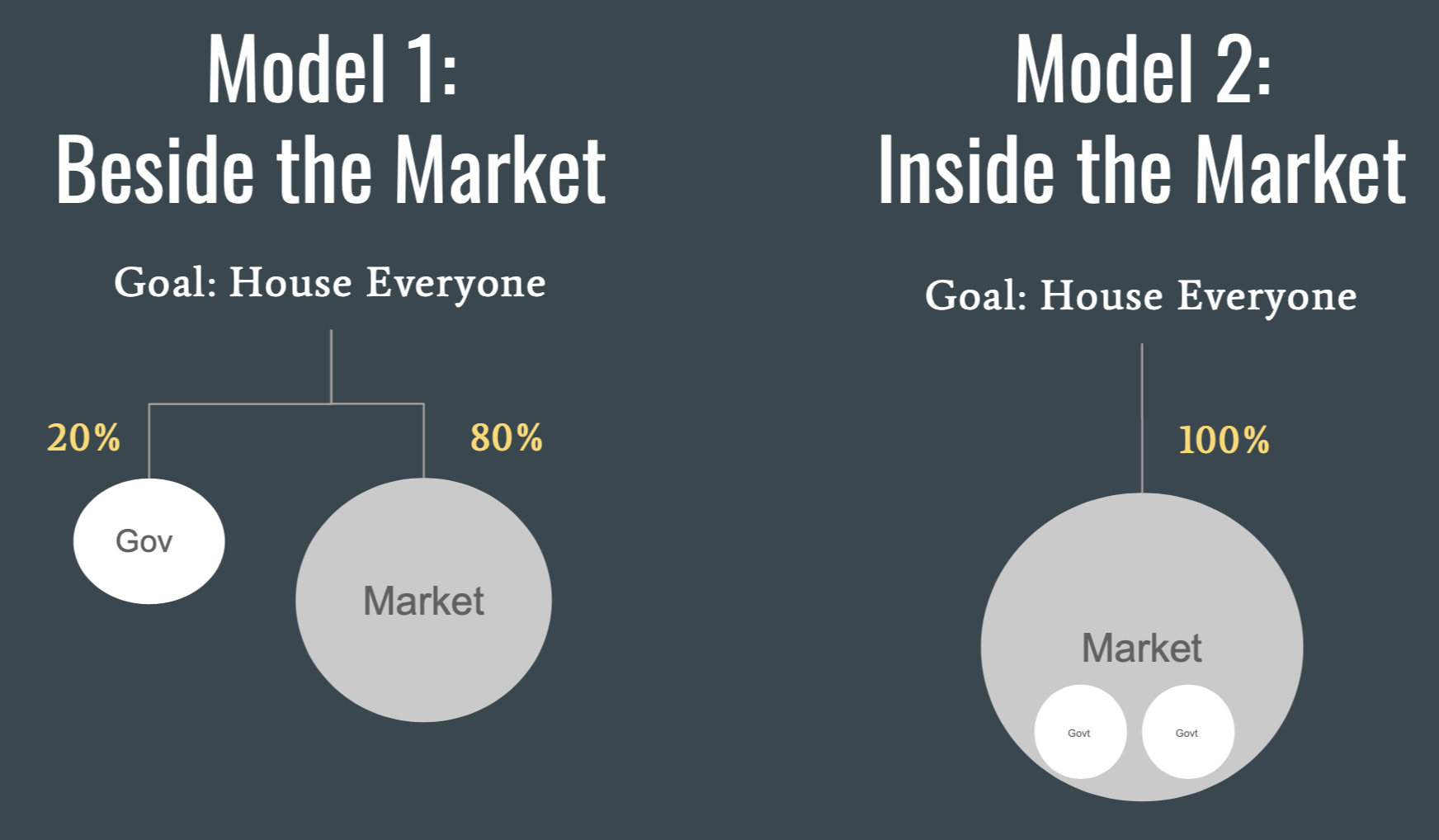

Government Housing | Last week we looked at the economics involved in the state building houses alongside the private market, rather than purchasing housing from within the private market. This week the Land Development Agency has announced a start date for work on 600 state-built houses near the Dublin/Wicklow border. They announced that “on completion, this will be the largest public housing scheme in the State.” More of this please.

💡 Interesting Links

Cassandra | If you’ve watched The Big Short, Michael Burry was played by Steve Carell in the movie that showed him predicting the crash and great recession of 2008. He’s still quite an active commentator and in the last year or so he has been ringing the alarm bells again. He argues that, because the economy was dramatically inflated beyond its actual, underlying productive capacity, we are only just getting started on a large market drop and ensuing recession. This video is a good summary of his arguments, and a good articulation of the worst case scenario.

Engineering Unemployment | Inflation is high because lots of people have spare money, but due to COVID in China, Russia’s war and other supply issues, the world economy isn’t able to make stuff fast enough to meet their demand. It’s possible that even without the supply issues, there would still be more money (and demand) than the global economy is equipped to meet. So too much money and not enough capacity to supply lead to inflation.

One way to solve this is to fix all of our supply chain problems and invest in our productive capacity but a) that will take some time and b) it’s not something central banks have the power to do. Something they do have the power to do is make people have less money.

Because of this, many central banks have been calling on Governments to do the first set of those things – fix supply constraints. In turn, people have been calling on central banks to make people have less money, by raising interest rates and causing a recession. Larry Summers, the former Treasury Secretary (finance minister) in the US, for example, has called for it quite explicitly:

“We need five years of unemployment above 5% to contain inflation — in other words, we need two years of 7.5% unemployment or five years of 6% unemployment or one year of 10% unemployment,”

I think this is a very grim thing to call for, but I don’t underestimate the number of people who might find it appealing. Inflation is broad and hurts everyone a little bit, but unemployment only hurts a small number (a lot). I’m sure the Larry Summers of the world never envision that they’ll be part of the 5% unemployment rate that they’re calling for, and so it could be an argument that gathers steam.

Luckily, I don’t see either the US Fed or the ECB signalling that they’ll go this far. There’s a big difference between bringing rates up a bit from zero, and deliberately engineering a recession. Let’s hope they don’t succumb to the pressure.