If I want to redesign the look and feel of this newsletter, I might hire a freelance designer. If I find an excellent one based in New Zealand, how would I pay her? I live in a part of the world where we believe money is called “a euro” and she and her fellow Kiwis do business using New Zealand dollars. I get paid in euro, but she wants to get paid in NZ dollars. So I first need to find someone who has NZ dollars and is willing to exchange them with some of my euros. I visit a marketplace, called a foreign currency exchange, where many people are willing to trade with me.

There is a going rate for NZ dollars relative to euros, which we call the exchange rate. If many people like me are trying to buy goods and services from New Zealand, or visit there on their holidays, there will be a lot of demand for a finite supply of NZ dollars and so their value will go up. In this way, the strength of the NZ dollar is linked to how much the country is exporting.

But that’s only half the picture. This is a two-way exchange, so the strength or weakness of the euro is also an important factor. Is the euro in demand? Are people trying to get their hands on euros so that they can buy French wines and Dutch bikes and visit the Colosseum?

In this way, being a eurozone member can be strange. The ability of an Irish writer to hire a designer in New Zealand is deeply affected by the import and export activities in other European countries. In particular, it’s affected by the imports and exports of German industrial manufacturers, and they are not having a good time at the minute.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and our subsequent sanctions, has meant that all of the energy needed to make cars and machines is significantly more expensive. Lots of manufacturers are trying to exchange away euros, to buy energy, and are making our euros less valuable.

People are also worried that Germany will have to start rationing energy and therefore be able to build (and export) fewer cars, trucks and machinery and so the demand for euros would fall further.

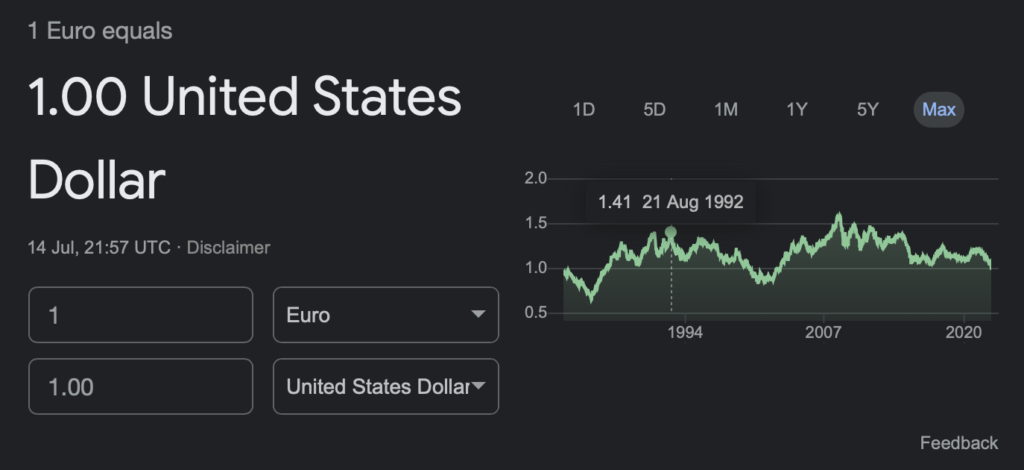

This, coupled with the fact that the US have slowed printing new dollars but the Eurozone has not, has meant that for the first time since 2002, the Euro and Dollar are now at parity. $1 = €1.

It’s cheaper for the Americans to come visit and for US MNCs to pay wages here, but it’s more expensive for us to buy things priced in dollars, in particular oil.

💡 Interesting Links

Political Central Banks | With the ECB raising rates yesterday for the first time in 11 years, Central Banks are back in the spotlight. Adam Tooze’s piece “The Death of the Central Bank Myth”, originally published at the start of the pandemic, is a timely read. He reminds us that the notion of a Central Bank as an non-political, independent building full of technocrats is a false one. The decisions of the Central Banks are inherently political. In fact, framing their choices as “merely technocratic” is a big political win in itself, for the supporters of their choices. The choice to fight inflation by raising interest rates is baked into the founding articles of the EU, and is correctly understood as a policy favouring savers over spenders, lenders over borrowers. As the ECB moves to raise interest rates (which helps savers) in an attempt to reduce inflation (high inflation benefits the indebted), we should recognise it as an action within a wider political philosophy, even if it’s one we agree with.

Vibe Shift | Is this the end of the era of Capital? Former hedge fund manager Russell Clark said this on a recent podcast:

“From the end of World War II to the 1970s […] you saw an emphasis on improving the experience of the worker, particularly relative to the corporates. So you saw rapidly increasing minimum wages and high corporate taxes. Pre-WWII was a period that preferenced Capital over labour, and the great depression was a period of falling wages, and the post-WWII period was one where we favoured labour over capital – look for full employment and rising wages when that happens. Then, with the Reagan and Thatcher Revolutions, the collapse of Communism, we then moved back to a period of favouring Capital over labour. In this context, you devalue your currency to combat inflation and make it competitive internationally. You have the exact same problem as we did in the great depression, but elongated over a longer period of time. […] Why do you see these regime changes? Because the votes aren’t there for the old one. After the 70s, when unions became to strong and that model stopped working, people voted for neo-classical policies. I would say, from 2016 onwards we’ve had a big shift [back towards labour].”

David McWilliams believes the same. “In short, labour is back and much of the inflation that we are likely to see over the coming year reflects this as workers try to claw back living standards in the form of higher wages. The pendulum which has swung far too much in favour of capital is swinging back towards employees and the future is likely to be one where profits are lower and wages are higher. It will take time before this is realised but the process is already under way.”

These both feel true, but my worry is that the ideology of pro-capital and pro-saver is deeply embedded in the operating rules of our central banks (as mentioned above).

Fun Philosophy | This site gives you increasingly absurd versions of the trolley problem. Link

Windfall Taxes |