Buckets of Spare Cash, But the Wrong Time to Spend

One model for thinking about Government spending is to consider how it redeploys resources, like workers, property and machinery, from one purpose to another. A machine digging for a new public road can’t also be digging a private garden. A person employed as a teacher can’t also be employed as a banker. An increase in Government spending causes resources to be redeployed from private sector use into public sector use.

At times of recession, when machinery lies idle, land is underused and unemployment levels are high, this redeployment almost always a very good thing, and the underpinning of “countercyclical” economic policy.

On the flip side, when the economy is near the limits of its capacity – when almost everyone who wants a job has one, when very few buildings are lying empty – then an increase in Government spending will struggle to attract those resources and redeploy them. Workers will need higher wages to attract them away from their current jobs, contractors and builders are all busy, rents are high and climbing.

That describes the situation we’re in now. Unemployment is at a 21 year low. Inflation is above 7% as we outbid each other for still limited resources.

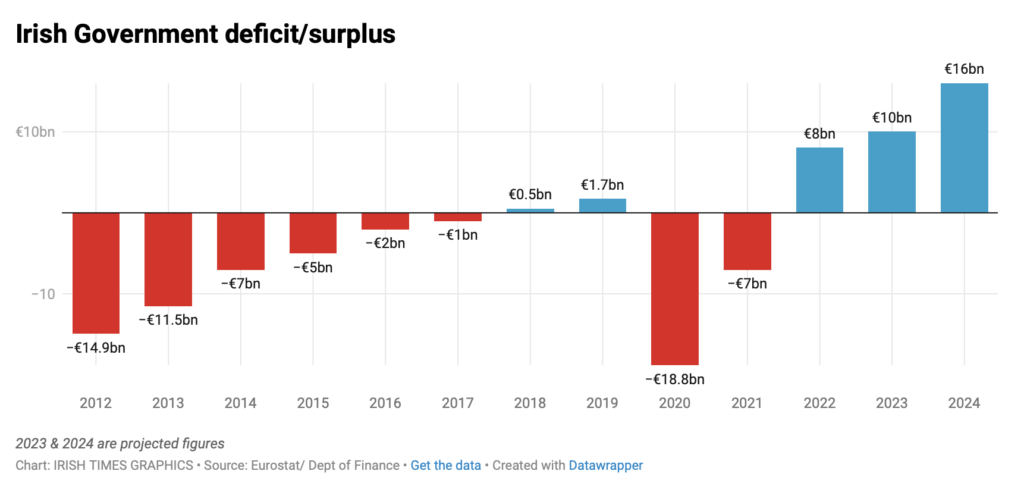

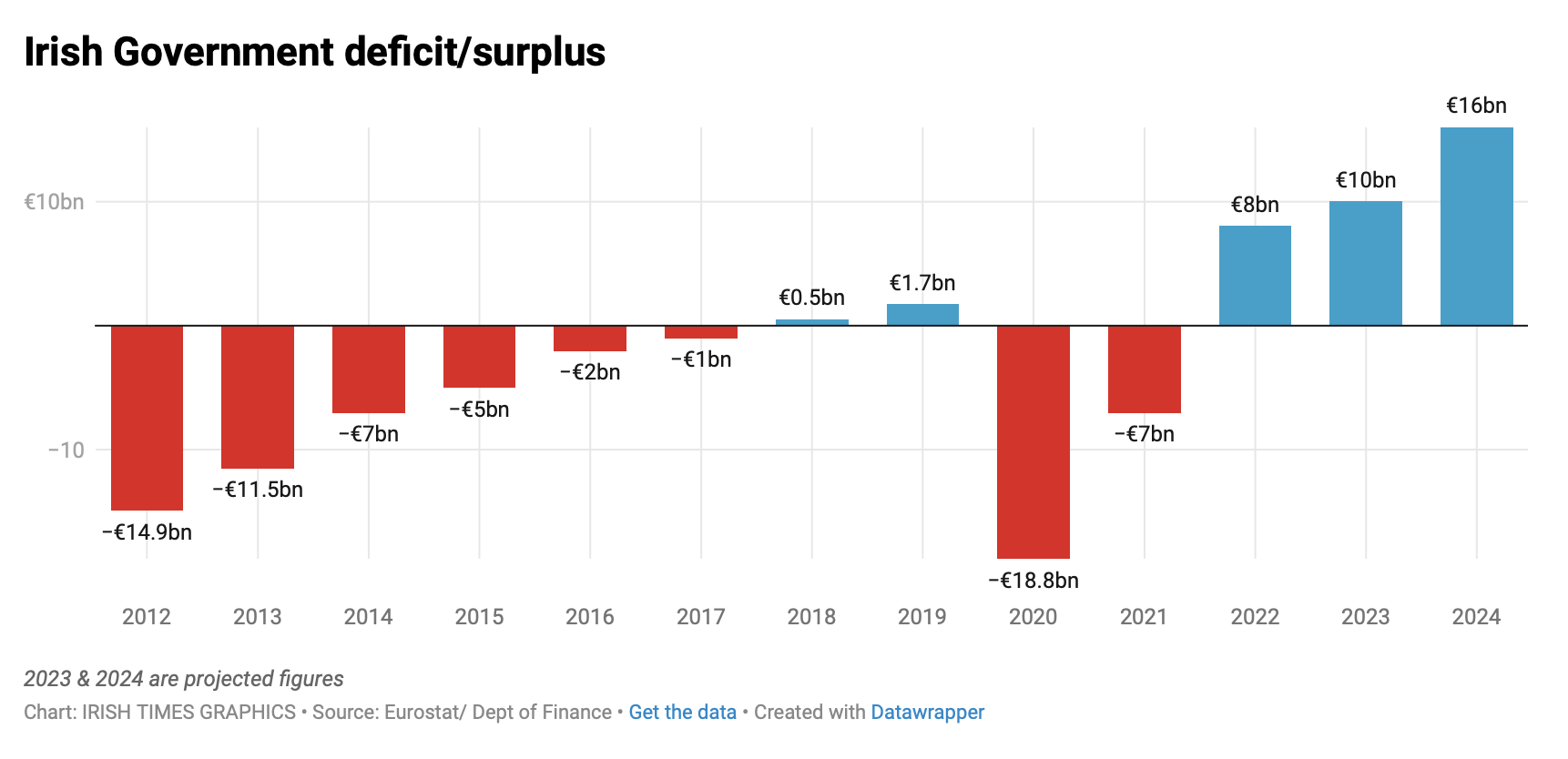

This is the background against which we find out that the Irish exchequer is getting, to use the technical terms, boatloads of extra cash from Corporate Taxes, which have now overtaken VAT as our second largest source of tax revenue, behind only income tax.

Image source: Irish Times

The temptation will be very high to find new, interesting and often very worthy ways to spend this money, but there is never going to be a more expensive time to try spend more Government money than now.

The fix for this is to dramatically increase our country’s productive capacity – by importing workers with attractive immigration policies, building them (and everyone else) houses and continuing our growth, to unblock key bottlenecks in An Bord Planeala.

But that fix doesn’t seem likely in the near term. The department of housing, for example, wasn’t even able to spend its current budget in the last two years – underspending by €1.5bn. So the less ambitious, but more achievable plan should be to run a high budget surplus over the next few years, sitting on the extra cash until investment is affordable. This could be coupled with tax increases on the highest earners and reduced spending in some areas, with exceptional spending increases for things that are so badly needed (i.e. housing) that it’s worth getting the expensive version now rather than the cheap version later.

- Irish Times: Surplus of over €16bn estimated for State for next year Link

- Business Post: Ireland’s budgetary watchdog warns against unbalancing economy Link (€)

- Irish Times: State needs to stop cost of living supports for better off families Link

- Business Post: The bottlenecks choking progress in housing, transport, planning, energy and water Link

More Local Buy-In = More Houses?

Robert Tolan, currently studying Irish housing supply at Trinity has written a suggestion for “Street Votes”, a form of hyper-local referenda on new housing. This seems quite counter to my priors, which imagines NIMBY-ism as a default and common position, which is why I found it such an enjoyable read.

- The Fitzwilliam: A Simple and Elegant Response to Ireland’s Housing Crisis Link

Stagnant Interest Rates

As we discussed before, the European Central Bank has been raising interest rates rapidly, but the interest rates on Irish mortgages haven’t risen nearly as fast. This is true for the interest Irish banks are paying on deposits too. Central Bank governor Gabriel Makhouf said that “One of the implications of the judgments [banks are making] is that lower rates that they are paying for deposits are subsidising the lower rates that they’re charging for mortgages.”

It seems that Irish banks have a uniquely high ratio of deposits to mortgages, so it makes more financial sense for them to keep interest rates on savings low, even if that loses them the chance to raise interest rates on mortgages.

- Irish Times: Low Irish deposit rates ‘subsidising’ mortgage holders, Makhlouf says link