96

💶 | Top Up Tax

Goodbye 12.5% Corporate Tax Rate (for some)<!–

View this email in your browser

This is a weekly(ish) newsletter about the Political Economy. See more or subscribe at petertanham.com

<!–

–>

📰 Trending News

Irish economic news, in summary and context.

House Prices are Flat, Hooray!

According to the latest Daft Report:

Listed prices nationally fell by 0.3% in the first quarter of 2023. This is the first time since 2013 that prices have fallen between December and March and the largest Q1 fall since 2012.

This is good news, showing a softening in demand (which I speculated last week could be driven in part by layoffs in the tech industry). Mortgage Interest rates still haven’t been rising very rapidly in Ireland, so any increase here could soften demand further.

On the flipside, however, the central bank increased their lending ceiling to 4x salary (for first time buyers) in January, which will add pressure on the average sale price as the year progresses, if not the number of sales.

This is a small but welcome reprieve, especially in the week that the eviction ban is being lifted. There is a real risk, however, that the supply of housing starts to decrease, when we desperately need it to continue growing at pace.

Irish Times: Asking prices for homes in Ireland fall for first time since 2013 Link

Daft: House Price Report Q1 2023 [PDF] Link

“Top Up” Corporate Tax Rate

A big story this week will be the increase in our Corporate Tax Rate this year. According to the Business Post, the Finance Minister will bring a proposal to cabinet this week for how we will raise the tax rate from 12.5% to 15%, but only on large multinationals with a turnover of €750m or more.

They’re calling it a “Top Up Tax.”

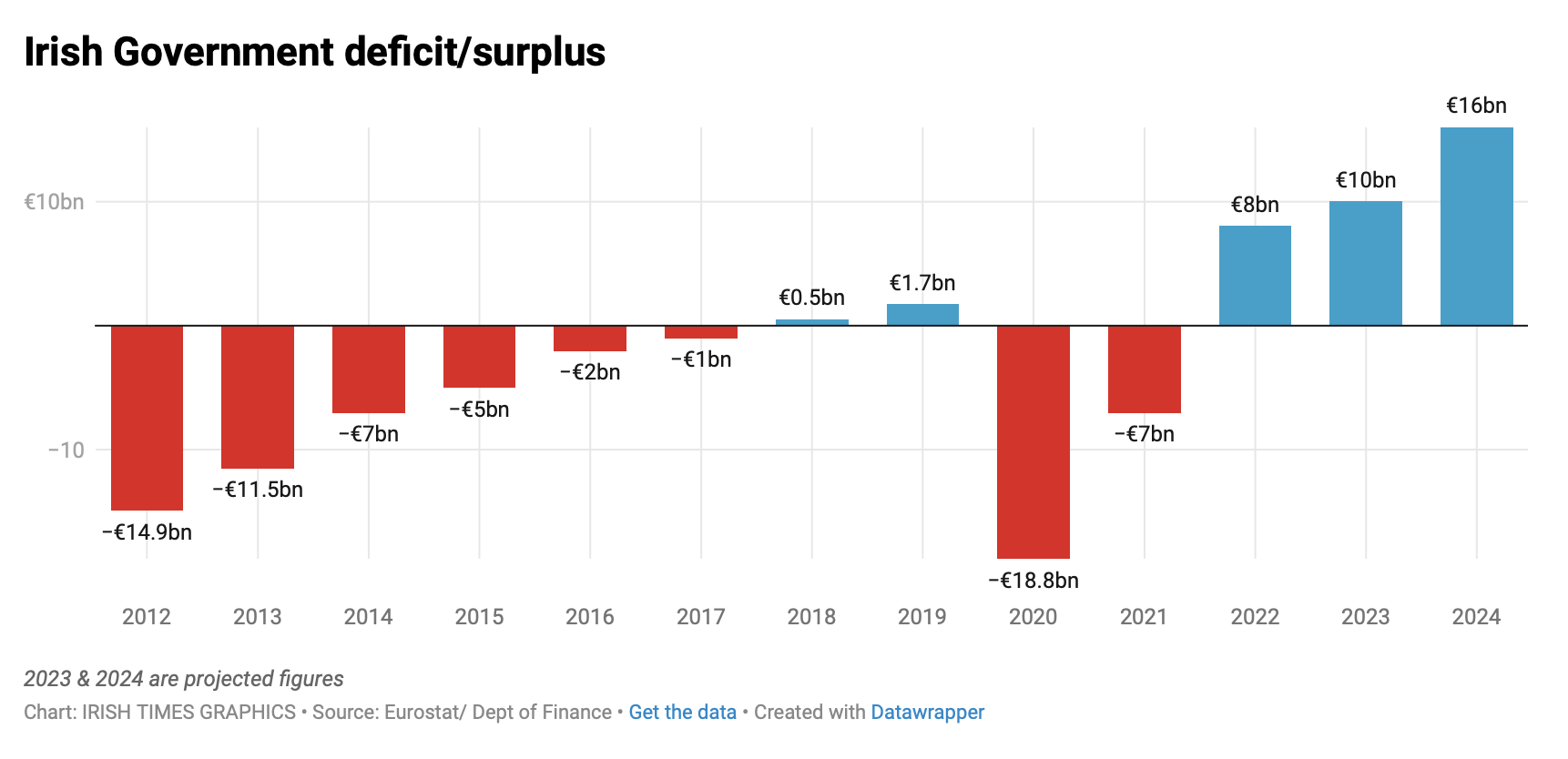

We’re doing this to align with the OECD agreement that all participating countries will charge at least 15%. This move poses a risk to the Government’s revenue from Corporate Taxes, which now runs at a whopper €22 billion(ish) per year. But the risk is unclear, and it’s even possible that the rate increase, because it happens everywhere, not just here, leads to an increase in our tax revenues.

The Department of Finance have some estimates of the loss we might face, but they mostly stress how difficult it is to calculate. Even their worst estimate would only bring us back to 2019 levels.

I’m looking forward to reading more about the proposal during the week. In particular why we’re taking the “top up” approach. We are going increase the tax rate for what I assume is the highest “flight risk” revenue, so why not do it for all?

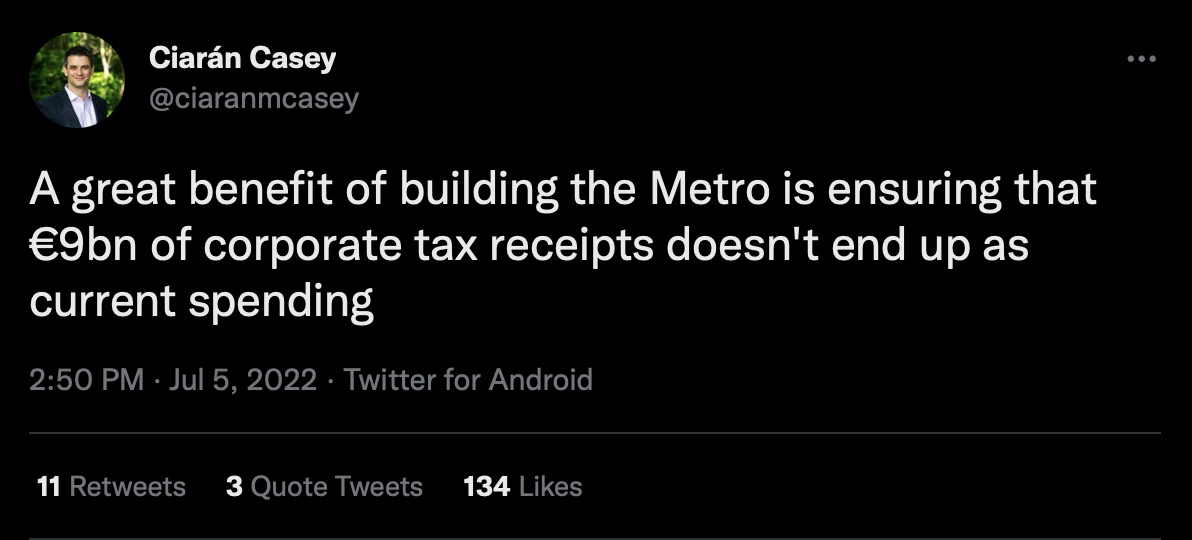

In the mean time, this is a great thread from Ciarán Casey on how Ireland ended up with our 12.5% corporate tax rate.

Business Post: ‘Mammoth’ task as McGrath moves on new 15 per cent corporate tax rate Link

RTE: ‘Historic’ corporate tax changes to take effect from next January Link

Irish Times: Ireland set to avoid implementing 15% headline corporate tax rate Link

Is Holly Right? Redux

Last week’s main story was the discussion of Holly Cairn’s observation that she is “a member of the first ever generation who will be worse off than my parents”. The debate rumbled on with Prime Time dedicating an episode to it during the week.

Aidan Regan, professor of political economy in UCD, says that it depends on what you mean by worse off. “What does it mean to say someone’s better off? I suppose we typically think about that in very material ways. And we could talk more broadly about whether or not Ireland is a better place to live today compared to previous generations. And I think they’re two very different things.”

RTE: Is this generation really worse off than their parents? Link

💡 What’s the New Idea?

New and notable progressive economic ideas from around the world.

The Slipperiness of Many Goals

In a previous newsletter (“Should Companies Be Political?”) I said the following:

Popular conceptions of capitalism are shifting, with many people considering a company’s responsibility to a wider group of stakeholders, like employees, local communities, the environment and the wider economy.

My personal politics likes a lot of this. In particular, the increasing acknowledgment that environmental sustainability is a responsibility of corporations too. However, I don’t think we acknowledge the trade-off we’re making and the risk we’re creating if we advocate a multi-stakeholder approach.

Often the winner in this move is the CEO and senior management. In a more “1980’s” version of capitalism, when we measured CEOs against a single goal of maximising shareholder value, it was a crude yardstick, and didn’t produce ideal societal outcomes, but it had the distinct advantage of being simple and measurable.

Whereas before the CEO could get fired when the share price dropped, they now have the flexibility to argue that they’re doing a good job because they were balancing shareholder value against the interest of some other group of stakeholders. It’s a lot of extra wiggle room, which reduces accountability and concentrates power.

There is huge uncertainty in the shift from a single metric to a multitude and the trade-offs involved. Most of these trade-offs manifest as a power struggle. There is simplicity in a single metric, but multiple-metrics give space for the question of who gets to decide what metrics are important, and how they rank against one another.

I worry about this when we (rightly) point out the flawed over-reliance on GDP as a single metric and propose to replace it, for example.

This week the National Bureau of Economic Research in the US published new research that documents this trend and substantiates the idea of multi-metric approaches as deflection.

Using natural language processing, we identify corporate goals stated in the shareholder letters of the 150 largest companies in the United States from 1955 to 2020. Corporate goals have proliferated, from less than one on average in 1955 to more than 7 in 2020.

We find goal announcements are associated with management’s responses to the firm’s (possibly changed) circumstances, with the changing power and preferences of key constituencies, as well as from management’s attempts to deflect scrutiny.

Goals also do seem to be announced opportunistically to deflect attention and alleviate pressure on management.

NBER: What Purpose Do Corporations Purport? Evidence from Letters to Shareholders Link

Central Banks are Recognizing “Greedflation”

Many times this year we’ve discussed the success of “Corporate Greed is Causing Inflation”, as a counter-narrative to “Wage Spirals are Causing Inflation”. This has been the view of prominent progressive politicians, commentators and economists, but not so much of central banks. It seems there have been some small changes on that front. In a recent interview with the New York Times, Fabio Panetta, member of the Executive Board of the European Central Bank said

“There’s a lot of discussion on wage growth,” Mr. Panetta said in an interview this week. “But we are probably paying insufficient attention to the other component of income — that is, profits.”

In the week that their own research showed that corporate profits “increased by 9.4% [in Q4] and contributed more than half” of inflation, you may think the statement “we’re probably paying insufficient attention” from a single executive board member is a little bit tepid… and you’d be right!

But it’s nothing compared to the wishy-washy statement from Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey in an interview this week:

“When companies set prices I understand that they have to reflect the costs that they face. But what I would say, please, is that when we are setting prices in the economy and people are looking forwards we do expect inflation to come down sharply this year and I would just say please bear that in mind.”

Compare that to his comments last year ago about wages:

“I’m not saying nobody gets a pay rise, don’t get me wrong, but I think, what I am saying, is we do need to see restraint in pay bargaining otherwise it will get out of control.”

“We are looking, I think, to see quite clear restraint in the bargaining process because otherwise, as I say, it will get out of control. It’s not at the moment, but it will do.”

Of course, ensuring markets are competitive and profiteering isn’t destructive isn’t the role of the central bank, but what they say about inflation and its drivers carries huge weight.

Guardian: Bank of England boss urges firms to hold back price rises or risk higher rates Link

FT: Central bankers warn companies on fatter profit margins Link

NYT: Are Big Profits Keeping Prices High? Some Central Bankers Are Concerned Link

CBS: U.S. companies just had their best year since before most of us were born Link

ING: Never waste a good crisis – a profit-price spiral in Germany Link

ECB: “Interview with The New York Times” Link

The Banking Crisis Rumbles On

Silicon Valley was the second largest banking collapse in US History. The third largest also happened in March, the collapse of Signature Bank. Joseph Politano describes:

although both banks had concentrated depositor bases, a large share of uninsured deposits, and had sustained significant losses and deposit outflows in recent quarters, Signature did not make the same kind of large unhedged bets on long-term assets that crushed SVB when interest rates rose. Instead, it had a more concentrated exposure to New York commercial real estate and private equity lending markets and was a key player in the crypto industry, all of which made it weaker than most but stronger than SVB in the current market environment.

As a sign of the heightened level of fear, more than $286bn has flooded into money market funds, presumably out of deposit banks, as they are presumed to be safer. Given that the largest run in US History was on money market funds, this doesn’t make me feel much safer.

Joseph Politano: What Killed Signature Bank? Link

FT: Money market funds swell by more than $286bn amid deposit flight Link

The Economist: “After Credit Suisse’s demise, attention turns to Deutsche Bank” Link

<!–

–>

Like This? Subscribe!

<!–

–>

Follow on Twitter

<!–

–>

Copyright © 2023 Peter Tanham, All rights reserved.

Want to change how you receive these emails?

You can update your preferences or unsubscribe from this list.