A simple way to think about the job of Minister for Housing is that their primary objective is to ensure all people in the country have a home. For a portion of the country, they’ll own that home (or a family member will), and for a portion it will be rented. In both types of housing – owned and rented – the vast majority of provision will be through private actors in a regulated housing market. People and companies sell and rent housing to each other. Some portion, however, will need to be provided by Government. In every developed country that I’m aware of, Governments either fill this gap, or there exists large amounts of homelessness (or low quality private housing, like trailer parks).

If you’re the housing minister, what are your options for filling this gap? One model is direct provision. Your housing ministry or department pays to build houses. Either by directly employing builders, or subcontracting it out, or through local Government. The burden of financing falls to you, but you get control of the housing at the end. The second model is by buying or renting them through the housing market.

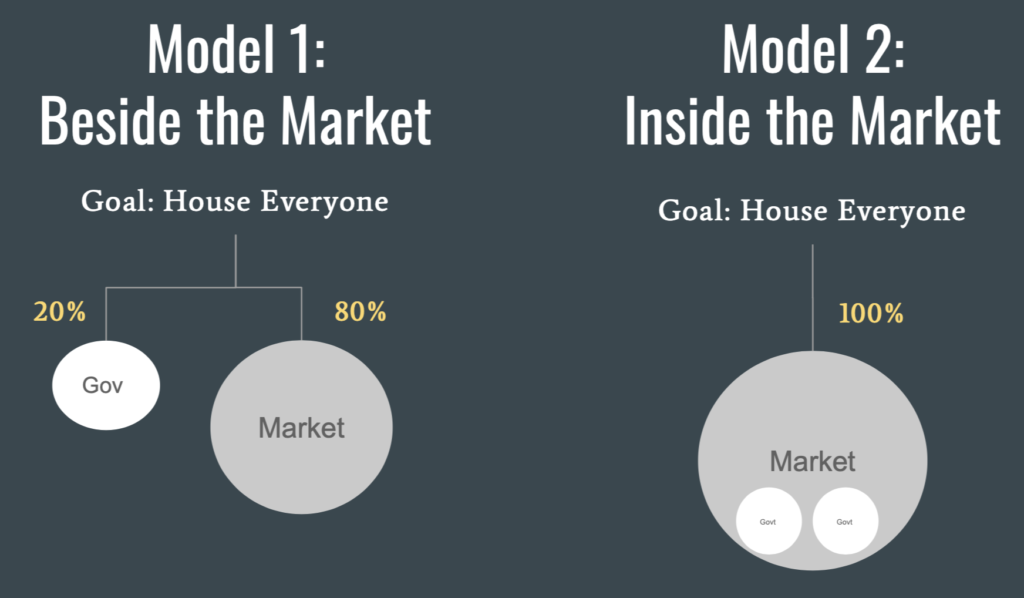

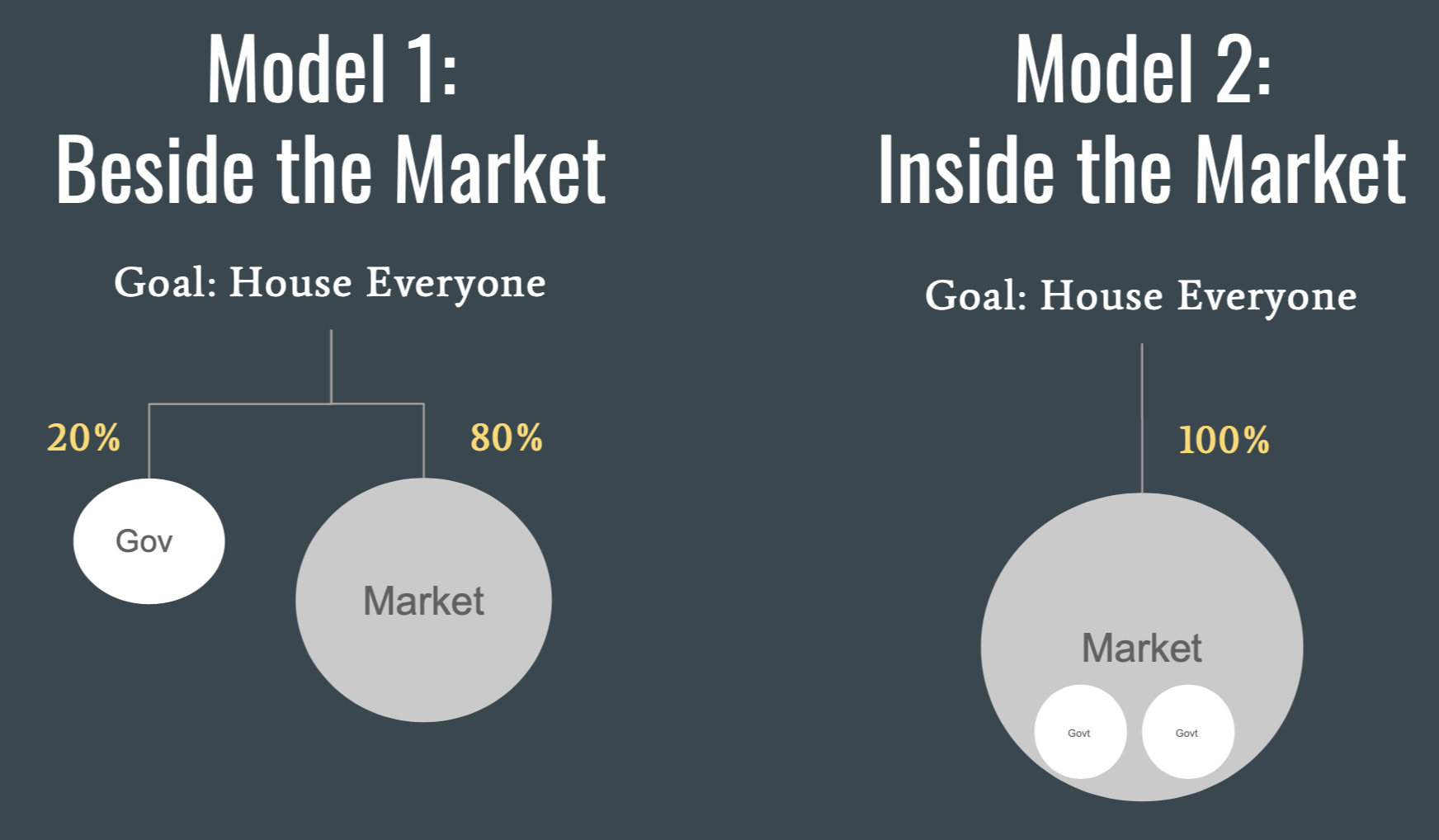

I’ve illustrated these two options below (with illustrative numbers), where in the first option Government supply of housing sits alongside the private supply of housing, whereas in the second all supply is driven by the private housing market, and Government acts within that, through several of these schemes.

In Model 1 you, as minister for housing, have to find the money to build this housing up front (often by borrowing it), which is why Model 2 is often more appealing. Private actors finance the housing supply and then the Government buys it directly, or subsidises its purchase/leasing.

In the past, the Irish Government operated something that looked more like Model 1, with the old Corporations building huge volumes of housing over the last 100 years. Although the cost was more upfront, this approach had very many benefits. By sitting alongside the private market, as an alternative source of supply, Government Housing (a.k.a. Social Housing) acted as a competitor and an anchor for pricing. It used the same pool of resources, but ultimately increased supply to the benefit of renters and purchasers.

Model 2, however, has been the primary model since roughly 2010. One of the main “acting within the market” programmes is the Housing Assistance Payment (HAP). From the HAP website:

“Under HAP, local authorities will make a monthly payment to a landlord […] on a HAP tenant’s behalf. In return, the HAP tenant pays a weekly contribution towards the rent to the local authority.”

This means that, at a time of very limited housing supply, people who are trying to find a house or apartment to rent are actively competing against the Government. Instead of acting as an anchor to drag prices downward, Government policy is bidding up prices and reducing market supply.

So should we stop this policy? It’s been over a decade since we did direct supply (model 1) in any meaningful numbers, so there is no alternative way to house the current recipients. We’re stuck paying €0.9bn in rent subsidies per year to house 100,000 people, with no ambitious plans to dramatically increase supply.

In many ways renters are paying much higher rents to subsidise Government housing. A tall burden on a small and generally less-well-off portion of the market, which should ideally be funded by broader general taxation instead. But to stop it now would be to pull the rug out from underneath an even more vulnerable population. This is the HAP conundrum.

All of this is to say that last week the minister decided to increase the HAP payments by about 40% in some areas. Some politicians have said this is not enough, others have said it’s too much. The tragedy is they’re probably both right.

💡 Interesting Links

Unreal GDP | This chart is a great illustration of the how disconnected Irish GDP figures have become from the lived economic experience of the average person. Our GDP went up far more than our peers, but our individual consumption dropped. (via John O’Brien)

Who Do Colleges Make Richer? | The Parliamentary Budget Office have done some very interesting analysis on higher education in Ireland. They have borrowed a model from the UK which looks at the socio-economic status of people before and after attending each college to assess which ones drive the most economic mobility within the country. So an institution will score well if a) it accepts more people from poorer backgrounds and b) it helps them earn more after graduating.

This feels like a good metric to help measure bang-for-our-buck when looking at the €2bn in annual Government funding of higher education. Obviously money isn’t the only benefit of a good education, but it sure helps. Trinity and UCD graduates tend to earn more than the average, but neither score highly on this rating because, while about 15% of leaving cert students are from disadvantaged areas, only 5% of students in either university are. This applies to courses too, for example, “only 4% of both medicine and economics undergraduate students come from disadvantaged areas”.